WASHINGTON — Some of the nation’s leading coral scientists stressed Thursday that the situation facing coral reefs is nothing short of desperate — and a drastic cut in global carbon dioxide emissions won’t be enough to protect corals from deadly bleaching events and other environmental threats.

In hopes of giving the reefs a fighting chance, a newly formed committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine will review a variety of potential intervention strategies, from genetic modification of coral species to spraying salt water into the atmosphere to shade and cool reefs.

At the committee’s first meeting on Thursday, Mark Eakin, coordinator of the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s (NOAA) Coral Reef Watch, said the “severity” of what has occurred between June 2014 and May 2017 — the “longest, most widespread, and possibly the most damaging” bleaching event on record — has changed the scientific community’s perspective about what should be done.

“The dire situation is here now,” he told the 12-person committee at its first meeting on Thursday. “We know that climate change is accelerating and accelerating bleaching. And so we need to make sure that this study isn’t something that talks about some nice areas of science but is too little and too late for the corals.”

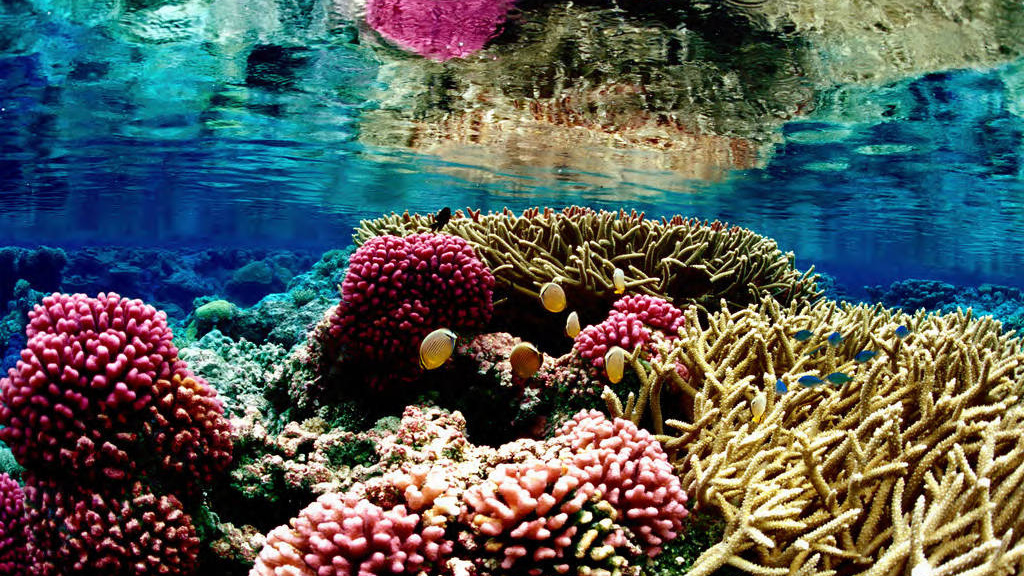

Coral bleaching is a phenomenon in which stressed corals expel algae and turn white, often as a result of warming ocean temperatures. If not given time to recover, bleached corals can perish. The recent event — just the third global bleaching event in recorded history — devastated reefs around the globe. Among the hardest hit was Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, where 93 percent of corals were impacted by bleaching and an estimated 29 percent of shallow water corals perished.

Often called “rainforests of the sea,” coral reefs provide habitat for more than 25 percent of the planet’s marine species and generate goods and services valued at $375 billion each year.

The project, titled “Interventions to Increase the Resilience of Coral Reefs,” is expected to take up to two years and will assess both the risks and benefits of intervention strategies. It is sponsored by NOAA.

Tom Moore, manager of NOAA’s Coral Reef Restoration Program, said the agency’s position is that saving the world’s reefs will require a multi-pronged approach that includes “immediate and aggressive action” to combat climate change, ongoing restoration and more drastic measures.

“We are trying to buy time here until hopefully we get things in check on a global scale,” he said.

Although still hopeful, Moore and others are realistic about the challenges ahead. They stressed that the enormity of the problem and a lack of resources means the scientific community will face tough decisions.

A recent United Nations-backed study found that “annual severe bleaching” will impact 99 percent of the world’s reefs within the century if humans do not take swift action to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

“Tomorrow’s reefs are not going to look like yesterday’s reefs,” Moore said.

A snorkeler swims over a dead coral reef in May 2016 after a bleaching event.

Among the “radical intervention” techniques Eakin highlighted in his presentation were Australia’s plan to circulate cool ocean water onto a handful of critical reef sites and another idea to spray ocean water into the air to create aerosol particles that would shade and cool reefs during bleaching events.

The most sobering appeal came from Joanna Walczak, a regional administrator at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Over the last three years, she says she helplessly watched the majority of the reef-building corals off Florida’s southeast coast collapse due to an unknown disease outbreak.

“I’ve gone through many, many different stages of grief, from visceral sadness to disbelief and anger. I’ve definitely had some despondence and actually was planning for a career change because I really, truly didn’t see hope for a while there,” she told the committee via a video feed. “But I’ve ultimately come through all of that and have made it back with focus and determined action to do everything in my power to make a difference with whatever little time we have left.”

Florida is already out of time, Walczak added. And with the rate that corals are currently being lost, officials there have had to completely shift their management strategy, from reactive to proactive. Among the ideas being entertained are large-scale disease treatment on the largest coral colonies and culling, which Walczak said means “specifically sacrificing some to potentially save the rest.”

“I’m going to make a really hard ask of you all,” she told the committee. “I need precautionary principle-based, expert-opinion-derived leaps of faith. Because after all I’ve seen, I’m ready to take these risks now.”

The study by the National Academies kicks off as the Trump administration abandons the Obama administration’s efforts to combat climate change and works feverishly to promote fossil fuel production in its quest for “energy dominance.” President Donald Trump — who famously dismissed climate change as a Chinese hoax in 2012 — has surrounded himself with like-minded climate change skeptics, including Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, who this week suggested global warming may be beneficial to humans.