A self portrait of Michelangelo has been discovered – hidden in one of his famous sketches for 500 years.

The sketch is disguised in a drawing of the artist’s close friend, Vittoria Colonna, on display in the British Museum.

An expert claims to have spotted it for the first time.

He suggests the caricature of the great Italian Renaissance artist may serve as a tool for analysing his probable bodily dimensions and may even provide clues as to his state of health at the time.

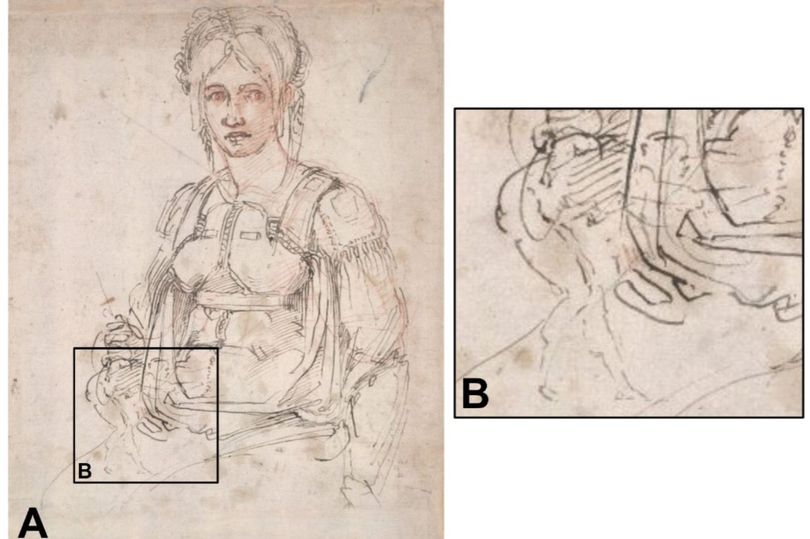

In the Vittoria portrait, a small figure can be seen standing in the area immediately in front of her stomach, and between the lines that form part of her dress. It had lain undiscovered for centuries.

Leaning forward at an acute angle, as if he himself were doing the drawing, lead author Dr Deivis de Campos said the caricature may have been a signature of sorts.

During Michelangelo Buonarroti’s time there were many restrictions on artists, perhaps the main one being were not allowed to sign their work.

Dr de Campos, of the Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre, Brazil, said a similar self portrait appeared in another of his most famous drawings.

He illustrated a sonnet intended for close friend Giovanni da Pistoia, alongside which he depicted himself painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Dr de Campos said: “The specialist literature has treated this famous caricature as the only known representation of the artist.

“Therefore, some authors have used it as a tool for analysing the artist’s probable bodily dimensions and even his state of health during the period in which he painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.”

Now Dr de Campos says Michelangelo included a similar self-caricature in another of his drawings, depicting Vittoria.

He said: “Among the many Michelangelo drawings in the British Museum collection is one that is less well known but nevertheless deserves special mention, especially because it is thought to depict a celebrated close friend, Vittoria Colonna.

“In this portrait made in 1525, a figure remarkably similar to that drawn by the artist in 1509 for his friend Giovanni da Pistoia stands in the area immediately in front of her abdomen and between the lines that form part of her dress.

“The only significant difference between the caricatures is the posture; in the drawing depicting Vittoria Colonna the caricature leans forward at an acute angle, as if the caricature itself were drawing the portrait of Vittoria Colonna.”

Dr de Campos said the Catholic Church in particular frowned upon artists signing their works to protect them against pride, one of the seven deadly sins.

But the patron who paid for the work had his name, image or symbol of his family displayed prominently. This was the main reason why many artists of that era discreetly inserted their own faces within their works.

In some cases, for example paintings by Botticelli and Rafael, this was obvious, since they had the consent of their patrons. In other cases it was not so apparent.

Another well-known Michelangelo self-portrait appears in a sculpture featuring a hooded figure and Jesus Christ. It was painted towards the end of his life in 1564.

But the descriptions in the catalogues from the British Museum referring to the portrait of Vittoria make no mention of any possible self-caricature of the artist.

Dr de Campos said it is “almost imperceptible at a quick glance”, and any observer who noticed it within the folds of the dress would have to be familiar with the other caricature drawn in 1509 for Giovanni da Pistoia to realise how similar they are.

He said: “If the two drawings were exhibited side by side, then sooner or later someone – not necessarily a specialist in Michelangelo’s works – would find significant similarities between the image hidden in the portrait of Vittoria Colonna and the self-caricature of Michelangelo from 1509.”

Many authors have pointed out most of Michelangelo’s works include various hidden symbols often associated with pagan, Neoplatonic beliefs, mathematical properties, and anatomical representations.

But none have mentioned the probable self-caricature of the artist inserted in his drawing of Vittoria.

Dr de Campos made the discovery thanks to extensive bibliographical research on the artist, as well as a a visit to the Casa Buonarroti museum in Florence, to investigate texts about this period of the artist’s life.

Michelangelo met Vittoria while living in Rome and their friendship grew stronger and stronger until her untimely death in 1547.

They exchanged long letters, wrote poems in honour of each other, and on many occasions exchanged poems, gifts and favours.

Many historians who wished to deny Michelangelo’s love for men chose to use his

poems for her as proof of his heterosexuality. But their love was purely platonic, added Dr de Campos.