One day in mid-2016, Robin Woods drove seven hours from his home in Maryland to visit a man named Mark Stevens in Amherst, Massachusetts. The two had corresponded for years, and they’d spoken on the phone dozens of times. But they had never met in person. Woods, who is bald and broad shouldered, parked his car and walked along a tree-lined street to Stevens’s house. He seemed nervous and excited as he knocked on the door. A wiry man with white hair and glasses opened it.

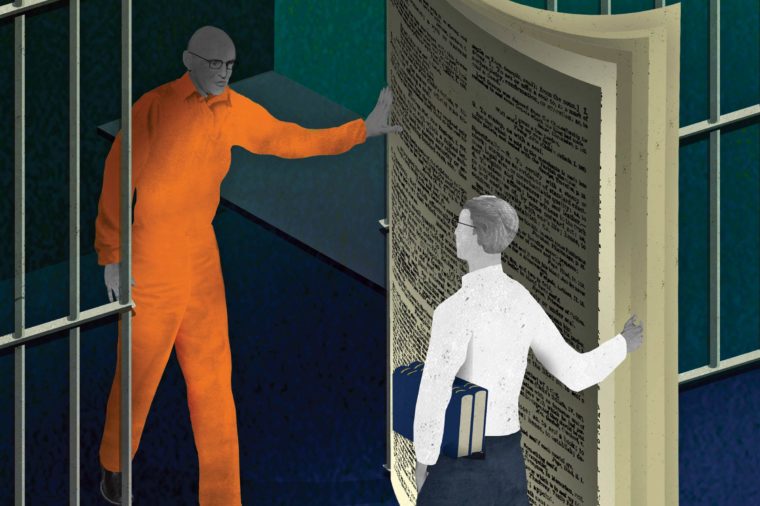

Within a few minutes, Woods, 54, and Stevens, 66, were sitting in the living room, talking about books. The conversation seemed both apt and improbable: When Woods had first written to Stevens, in 2004, he was serving a 16‑year prison sentence in Jessup, Maryland, for breaking and entering.

And yet it was a book that had brought them together.

At Jessup, Woods had bought and begun reading Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Encyclopedia, a nearly five-pound tome that starts with an entry on the German city of Aachen and ends with zymogen, an inactive protein precursor to enzymes. He hoped to read all its alphabetical entries, which exceeded 25,000, and he spent hours flipping through the pages. One day, he was puzzled to read an entry stating that the 11th‑century ruler Toghrïl Beg had entered Baghdad in 1955. He quickly realized that it should have been 1055. “I read it several times to make sure,” he says. Then he turned to the masthead, which listed the editor, Mark A. Stevens.

“Dear Mr. Stevens,” Woods wrote in a letter. “I am writing to you at this time to advise you of a misprint in your FINE!! Collegiate Encyclopedia.” He described the error and offered his thanks for Merriam-Webster’s reference books. “I would be lost without them,” he wrote, unsure whether he’d ever get a response.

What Woods didn’t mention in his first letter to Stevens was that the encyclopedia represented the culmination of his self-education. Woods grew up in a housing project in Cumberland, Maryland. Cumberland was once an industrial center but has become one of the poorest metropolitan areas in America. Woods was first sent to prison at 23, for firing his grandfather’s rifle through an apartment window after a drug-related dispute. He was young, embittered, and almost completely illiterate. “I had never read a book in my life,” he says.

Woods remembers enjoying first grade, but he says he was bullied because of his light skin. (Woods was raised by his mother, who was African American. His father was of mixed race.) In second grade, he developed an antagonistic relationship with his teacher, who made him sit in a coat closet whenever he annoyed her. Eventually, the school transferred him to a special education program. As he progressed through the grades, instead of learning to read and write, he was given chores such as collecting attendance slips and stacking milk in the cafeteria refrigerator. These tasks earned him mostly A’s and B’s. “Of course, I didn’t learn nothing,” he says. “They say it takes a community to raise a child. It takes one to destroy a child too.” Woods ultimately dropped out of high school.

During his first stint in prison, Woods began his own course of study. He was sent to a notoriously harsh prison in Hagerstown, Maryland. He resented authority figures and often directed outbursts at the guards, who responded by putting him on lockup. For 23 hours at a time, and sometimes longer, Woods would be alone in a cell that had no television or radio. One day, a man with a cart of books wound his way through the lockup tiers, shouting, “Library call!” Woods wasn’t interested at first, but his boredom won out: He decided to borrow The Autobiography of Malcolm X and The Sicilian, a Mafia novel by Mario Puzo.

The autobiography proved “too complicated,” and The Sicilian was only slightly easier. Still, Woods persisted. “Many, many words I had to skip over because I couldn’t read them,” Woods recalls. Each page took him about five minutes but left him with a glow of accomplishment. By the time he got to the end, about a week had passed. “I remember that I wept,” Woods says—not because of what he had read but because he had succeeded in reading.

Woods soon bought his first dictionary at the prison commissary and began etching words into his memory by copying them down and reading them aloud. He read into the early hours of the morning. “Even though I was confined in a cell, my mind was free,” Woods says. “I could escape.”

For a brief time, Woods also regained his physical freedom. In 1987, he finished his sentence and moved back to Cumberland, where he lived in a shack and worked occasionally for a man who cleaned offices. Books had expanded Woods’s world, but they hadn’t made it any easier for him to stay out of trouble. One night, Woods says, he drove to one of the offices he’d helped clean, knocked out a window, and stole several thousand dollars’ worth of equipment.

The next day, he went to a local club and, over a game of pool, tried to sell some of the equipment. When a group of state troopers walked in the side door, he didn’t put up a fight. Not even two years had passed since his release, and Woods was once again incarcerated at the prison in Hagerstown—an institution he had come to detest. Because of his prior record, Woods received a harsh sentence: 16 years for two counts of breaking and entering. In 1991, after Woods got caught up in a prison riot, his sentence was extended by seven years.

There are a few ways that books enter prisons. They’re sold at prison commissaries and lent by prison libraries; nonprofits also distribute donated books to prisoners. There are state and federal restrictions, of course: In some institutions, hardcover books may be sent to an inmate only if they’re from a publisher, a book club, or a bookstore; the U.S. Bureau of Prisons also prohibits texts that are “detrimental to the security, good order, or discipline of the institution” or that “may facilitate criminal activity.” Many prisons also add their own idiosyncratic rules.

Even so, Woods managed to assemble a small library in his cell. “A lot of prisoners put emphasis on how many Nike shoes they have,” he says. “I would wear a pair of prison tennis shoes if necessary, but I had eight or nine hundred dollars’ worth of books.” Woods ordered his encyclopedia through the mail after reading about it in a catalog. When it arrived, he says, it was carefully inspected for contraband.

In late November 2004, when Mark Stevens received his first letter from Robin Woods, he responded on Merriam-Webster, Inc., letterhead. “I believe you’re the first to have spotted the error in the Toghrïl Beg entry; by 1955 Toghrïl was no longer exactly in his prime,” Stevens wrote. “Please stay on the lookout for more.” Woods was thrilled, and soon he wrote again, highlighting errors in the entries for Edward the Confessor and ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān—“not as a critic, but as a friend,” he explained in his letter. “For I believe that M.W.I. is the crème de la crème. I would like to help it to stay that away [sic]!”

Over the next two years, Stevens sent 18 letters to Woods; Woods sent several dozen to Stevens. They discussed the life of Cleopatra and the self-education of Malcolm X, but Woods barely discussed his criminal record, and Stevens never asked. “They were perfectly executed letters, and very courteous,” Stevens says. “It still seems astonishing to me.” One letter concluded, “I have the honor to be, Sir, your most obedient servant.”

But in 2005, it seemed as if all of that was about to change. Woods learned that he would be transferred, without a clear explanation, to a supermax prison in Baltimore. Officials told him he wouldn’t be allowed to bring his books.

Woods protested. Within days of arriving at his new cell, he went on a hunger strike. “I’ve gone crazy and will not eat until they allow me to keep my books,” he wrote to Stevens. Several weeks later, he wrote another letter, this one short and despondent: “I look like walking death. But I’m hardheaded and shall not give up.” Locked in a single room, Woods lost about 70 pounds.

One day, as Woods remembers it, he saw a shadow on the wall of his cell. It was the Maryland commissioner of corrections, who asked about his health. “He had a very curious look on his face,” Woods recalls. Finally, the commissioner asked, “Who is this Mark Stevens?”

Woods remembers thinking, How does he know Mr. Stevens? As it turns out, Stevens had written to two prison wardens, and eventually word had gotten to the commissioner, who called him. They spoke about Woods and the encyclopedia. Not long after that, the commissioner offered Woods a deal. If he would end his hunger strike and follow the rules for a year, the commissioner would cut short the extended sentence and send Woods home. In the meantime, his books would be restored to him.

“I feel like a kid getting out of high school,” Woods wrote to Stevens near the end of 2006. “The whole world is waiting for me!” In January 2007, 18 years after the start of his incarceration and five years before the scheduled conclusion of his extended sentence, Robin Woods was discharged from prison. He had about $50 to his name, the minimum required by law.

Woods once more moved back to Cumberland, where he was given housing by a local pastor. Every few months, he called Stevens. The calls continued for a decade before they finally arranged to meet.

When Woods visited Stevens at his home in Amherst in June 2016, they were soon acting like old friends. “I never met you until today, but I love you very much,” Woods told Stevens. “You’re a good man.” They took hikes, went to a play, and visited the home of Emily Dickinson, where a plaque quotes her lines: “There is no Frigate like a Book / To take us Lands away.” On Sunday, after a goodbye hug, Woods began the long drive home.

Woods rarely reads anymore—partly, he says, because it takes considerable effort just to pay the bills and keep clear of the law. But he still keeps a copy of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Encyclopedia close. “While my body is here in prison, my mind has seen the world,” Woods once wrote to Stevens. “There are a lot of places that I hope to see that I have read about in my many books.” Stevens responded by quoting another book, T. H. White’s The Once and Future King.

“The best thing for being sad,” Merlyn says in the novel, “is to learn something. That is the only thing that never fails.”