A landmark study is questioning the use of stents to treat stable angina.

Every year, about half a million people around the world undergo an invasive procedure called angioplasty with stent — or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) — to treat a heart condition known as angina. But according to new research, the treatment may not as effective as experts have long thought — in fact, it may not be effective at all.

The findings, published in the November 2017 issue of the journal The Lancet, are based on a blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of 200 patients called the ORBITA trial. When researchers compared PCI with a simulated procedure, they found PCI offered no significant added improvement of symptoms or quality of life compared to the placebo.

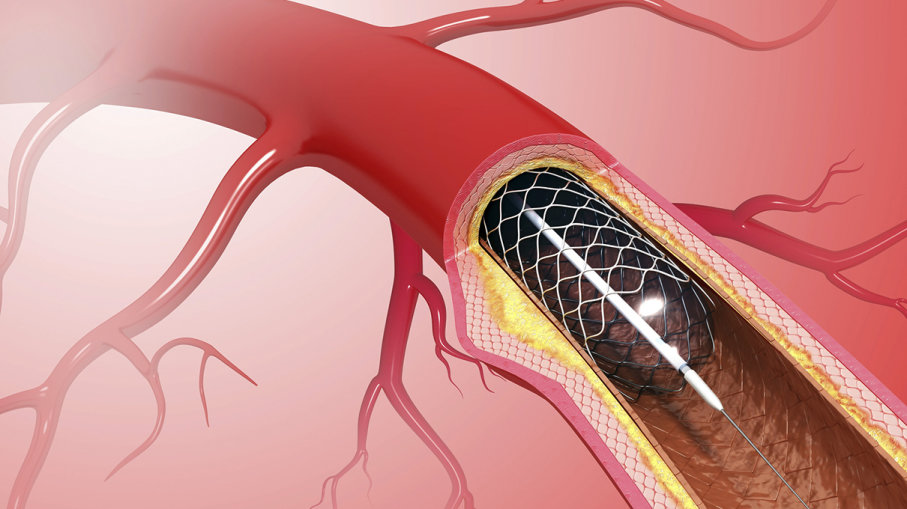

During PCI, tiny wire cages called stents are inserted into blocked arteries to open them up and improve blood flow. The procedure can save the life of someone experiencing a heart attack, but stents are more commonly used in patients with blocked arteries who experience chest pain under certain circumstances, like climbing hills or stairs. This is known as stable angina and is a common condition that describes chest pain resulting from overexertion. Usually it is a result of hardened, narrow blood vessels and fatty plaques building up in the arteries.

“The most important reason we give patients a stent is to unblock an artery when they are having a heart attack,” lead author of the study, Dr. Rasha Al-Lamee, told Imperial College London. “However, we also place stents into patients who are getting pain only on exertion caused by narrowed, but not blocked arteries. It’s this second group that we studied.”

Half of the ORBITA trial patients received the stent and half received the placebo, and all underwent exercise tests before and six weeks after the procedure. The tests monitored their heart and lung function and measured how quickly they could walk on a treadmill. The researchers looked for a change in the amount of time patients could sustain the workout post-procedure. Researchers expected the stents to improve blood flow to the heart and subsequently improve exercise performance — but Al-Lamee and his colleagues were confronted with some surprising results.

While the procedure increased participants’ overall exercise time by 28.4 seconds, and the placebo only increased participants’ time by 11.8 seconds, that difference between groups wasn’t statistically significant. That means researchers couldn’t say whether the effect was directly due to the stent or just random chance. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the improvement of patients’ symptoms, according to their own self-reports.

What the tests did confirm is that the use of stents significantly improved blood flow to the heart by opening up the coronary artery. But that improvement didn’t translate to better exercise capacity or improved symptoms.

“It’s a very humbling study for someone who puts in stents,” Dr. Brahmajee K. Nallamothu, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Michigan, told The New York Times.

But before patients protest the use of stents and doctors turn away from performing PCI, it’s important to know the study’s limitations. The participants took high doses of medication before the procedure, which the researchers say real-world patients may not do. Plus, all the participants involved had a single-vessel form of heart disease, so it’s unclear whether people with multi-vessel forms may experience different results from PCI. The researchers will continue to explore the data to see how it could impact patients in the future.

“It seems that the link between opening a narrowing coronary artery and improving symptoms is not as simple as everyone had hoped,” Al-Lamee told Imperial College London. “This is the first trial of its kind and will help us to develop a greater understanding of stable angina, a disease which affects so many of our patients every day.”